In the last two seminars we considered various approaches to happiness. We have discussed ancient philosophers who rule out pursuing happiness through base means, and who propose instead that one ought to pursue virtue at all costs because this is the only path to happiness. This first part of our seminars concludes with a consideration of the Christian approach to happiness. Can we be happy in this life? What problems do those who pursue happiness in this life face? What is needed in order to find true happiness?

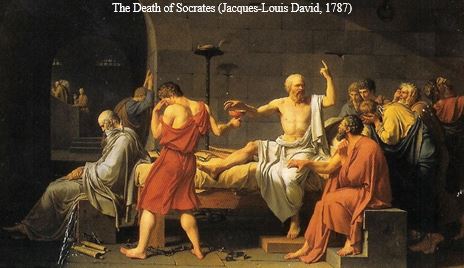

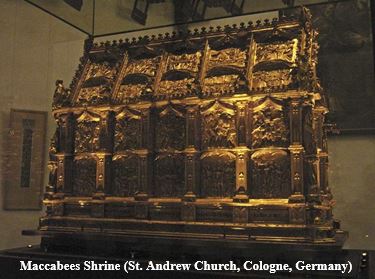

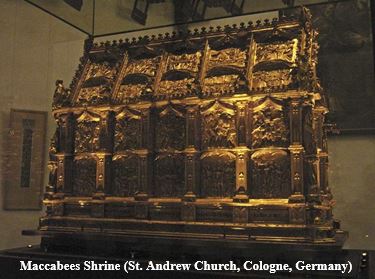

Maccabees Shrine (St. Andrew Church, Cologne, Germany)

The Holy Bible: 2 Maccabees 7:1, 2, 7-42

1 It came to pass also, that seven brethren, together with their mother, were apprehended, and compelled by the king to eat swine's flesh against the law, for which end they were tormented with whips and scourges. 2 But one of them, who was the eldest, said thus: What wouldst thou ask, or learn of us? we are ready to die rather than to transgress the laws of God, received from our fathers. 7[After the first had been put to death,] they asked [the second brother] if he would eat, before he were punished throughout the whole body in every limb. 8 But he answered in his own language, and said: I will not do it. Wherefore Ire also in the next place, received the torments of the first: 9 And when he was at the last gasp, he said thus: Thou indeed, O most wicked man, destroyest us out of this present life: but the King of the world will raise us up, who die for his laws, in the resurrection of eternal life. 10 After him the third was made a mocking stock, and when he was required, he quickly put forth his tongue, and courageously stretched out his hands:

11 And said with confidence: These I have from heaven, but for the laws of God I now despise them: because I hope to receive them again from him. 12 So that the king, and they that were with him, wondered at the young man's courage, because he esteemed the torments as nothing. 13 And after he was thus dead, they tormented the fourth in the like manner. 14 And when he was now ready to die, he spoke thus: It is better, being put to death by men, to look for hope from God, to be raised up again by him: for, as to thee thou shalt have no resurrection unto life. 15 And when they had brought the fifth, they tormented him. But he looking upon the king,

16 Said: Whereas thou hast power among men, though thou art corruptible, thou dost what thou wilt: but think not that our nation is forsaken by God. 17 But stay patiently a while, and thou shalt see his great power, in what manner he will torment thee and thy seed. 18 After him they brought the sixth, and he being ready to die, spoke thus: Be not deceived without cause: for we suffer these things for ourselves, having sinned against our God, and things worthy of admiration are done to us: 19 But do not think that thou shalt escape unpunished, for that thou attempted to fight against God. 20 Now the mother was to be admired above measure, and worthy to be remembered by good men, who beheld seven sons slain in the space of one day, and bore it with a good courage, for the hope that she had in God:

21 And she bravely exhorted every one of them in her own language, being filled with wisdom: and joining a man's heart to a woman's thought, 22 She said to them: I know not how you were formed in my womb: for I neither gave you breath, nor soul, nor life, neither did I frame the limbs of every one of you. 23 But the Creator of the world, that formed the nativity of man, and that found out the origin of all, he will restore to you again in his mercy, both breath and life, as now you despise yourselves for the sake of his laws. 24 Now Antiochus, thinking himself despised, and withal despising the voice of the upbraider, when the youngest was yet alive, did not only exhort him by words, but also assured him with an oath, that he would make him a rich and a happy man, and, if he would turn from the laws of his fathers, would take him for a friend, and furnish him with things necessary. 25 But when the young man was not moved with these things, the king called the mother, and counselled her to deal with the young man to save his life.

26 And when he had exhorted her with many words, she promised that she would counsel her son. 27 So bending herself towards him, mocking the cruel tyrant, she said in her own language: My son, have pity upon me, that bore thee nine months my womb, and save thee suck years, and nourished thee, and brought thee up unto this age. 28 I beseech thee, my son, look upon heaven and earth, and all that is in them: and consider that God made them out of nothing, and mankind also: 29 So thou shalt not fear this tormentor, but being made a worthy partner with thy brethren, receive death, that in that mercy I may receive thee again with thy brethren. 30 While she was yet speaking these words, the young man said: For whom do you stay? I will not obey the commandment of the king, but the commandment of the law, which was given us by Moses.

31 But thou that hast been the author of all mischief against the Hebrews, shalt not escape the hand of God. 32 For we suffer thus for our sins. 33 And though the Lord our God is angry with us a little while for our chastisement and correction: yet he will be reconciled again to his servants. 34 But thou, O wicked and of all men most flagitious, be not lifted up without cause with vain hopes, whilst thou art raging against his servants. 35 For thou hast not yet escaped the judgment of the almighty God, who beholdeth all things.

36 For my brethren, having now undergone a short pain, are under the covenant of eternal life: but thou by the judgment of God shalt receive just punishment for thy pride. 37 But I, like my brethren, offer up my life and my body for the laws of our fathers: calling upon God to be speedily merciful to our nation, and that thou by torments and stripes mayst confess that he alone is God. 38 But in me and in my brethren the wrath of the Almighty, which hath justly been brought upon all our nation, shall cease. 39 Then the king being incensed with anger, raged against him more cruelly than all the rest, taking it grievously that he was mocked. 40 So this man also died undefiled, wholly trusting in the Lord.

41 And last of all after the sons the mother also was consumed. 42 But now there is enough said of the sacrifices, and of the excessive cruelties.

READING QUESTIONS:

- 1. How do the seven brethren and mother face their cruel torture? What are they dying for? What would they rather do than betray God’s laws?

- 2. What allows this noble family to so confidently face death (be sure to consider the individual statements of each of them)? Consider whether a similar consolation is offered to the philosophers we discussed in seminar two.

St. Augustine (José de Ribera, 1635)

Excerpt from St. Augustine’s Confessions

Is it, then, uncertain that all men wish to be happy, since those who do not wish to find their joy in thee -- which is alone the happy life -- do not actually desire the happy life? Or, is it rather that all desire this, but because "the flesh lusts against the spirit and the spirit against the flesh," so that they "prevent you from doing what you would," you fall to doing what you are able to do and are content with that. For you do not want to do what you cannot do urgently enough to make you able to do it.

Now I ask all men whether they would rather rejoice in truth or in falsehood. They will no more hesitate to answer, "In truth," than to say that they wish to be happy. For a happy life is joy in the truth. Yet this is joy in thee, who art the Truth, O God my Light, "the health of my countenance and my God." All wish for this happy life; all wish for this life which is the only happy one: joy in the truth is what all men wish….

READING QUESTIONS:

- 1. Do all men wish to be happy? Why does it initially seem that they do not? How are truth and happiness connected, and how does the fact that all men avoid falsehood help establish a connection between truth and happiness?

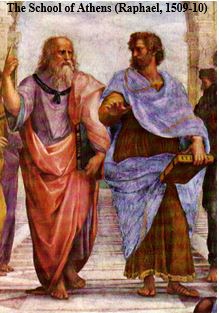

Excerpt from St. Augustine’s City of God

As I see that I have still to discuss the fit destinies of the two cities, the earthly and the heavenly, I must first explain, so far as the limits of this work allow me, the reasonings by which men have attempted to make for themselves a happiness in this unhappy life, in order that it may be evident, not only from divine authority, but also from such reasons as can be adduced to unbelievers, how the empty dreams of the philosophers differ from the hope which God gives to us, and from the substantial fulfillment of it which He will give us as our blessedness. Philosophers have expressed a great variety of diverse opinions regarding the ends of goods and of evils, and this question they have eagerly canvassed, that they might, if possible, discover what makes a man happy. For the end of our good is that for the sake of which other things are to be desired, while it is to be desired for its own sake; and the end of evil is that on account of which other things are to be shunned, while it is avoided on its own account…

If, then, we be asked what the city of God has to say upon these points, and, in the first place, what its opinion regarding the supreme good and evil is, it will reply that life eternal is the supreme good, death eternal the supreme evil, and that to obtain the one and escape the other we must live rightly. And thus it is written, "The just lives by faith," (Habakkuk 2:4) for we do not as yet see our good, and must therefore live by faith; neither have we in ourselves power to live rightly, but can do so only if He who has given us faith to believe in His help do help us when we believe and pray. As for those who have supposed that the sovereign good and evil are to be found in this life, and have placed it either in the soul or the body, or in both, or, to speak more explicitly, either in pleasure or in virtue, or in both; in repose or in virtue, or in both; in pleasure and repose, or in virtue, or in all combined; in the primary objects of nature, or in virtue, or in both,—all these have, with a marvelous shallowness, sought to find their blessedness in this life and in themselves. Contempt has been poured upon such ideas by the Truth, saying by the prophet, "The Lord knows the thoughts of men" (or, as the Apostle Paul cites the passage, "The Lord knows the thoughts of the wise") "that they are vain….”

For what flood of eloquence can suffice to detail the miseries of this life? Cicero, in the Consolation on the death of his daughter, has spent all his ability in lamentation; but how inadequate was even his ability here? For when, where, how, in this life can these primary objects of nature be possessed so that they may not be assailed by unforeseen accidents? Is the body of the wise man exempt from any pain which may dispel pleasure, from any disquietude which may banish repose? The amputation or decay of the members of the body puts an end to its integrity, deformity blights its beauty, weakness its health, lassitude its vigor, sleepiness or sluggishness its activity,—and which of these is it that may not assail the flesh of the wise man? Comely and fitting attitudes and movements of the body are numbered among the prime natural blessings; but what if some sickness makes the members tremble? what if a man suffers from curvature of the spine to such an extent that his hands reach the ground, and he goes upon all-fours like a quadruped? Does not this destroy all beauty and grace in the body, whether at rest or in motion? What shall I say of the fundamental blessings of the soul, sense and intellect, of which the one is given for the perception, and the other for the comprehension of truth? But what kind of sense is it that remains when a man becomes deaf and blind? where are reason and intellect when disease makes a man delirious? We can scarcely, or not at all, refrain from tears, when we think of or see the actions and words of such frantic persons, and consider how different from and even opposed to their own sober judgment and ordinary conduct their present demeanor is. And what shall I say of those who suffer from demoniacal possession? Where is their own intelligence hidden and buried while the malignant spirit is using their body and soul according to his own will? And who is quite sure that no such thing can happen to the wise man in this life? Then, as to the perception of truth, what can we hope for even in this way while in the body, as we read in the true book of Wisdom, "The corruptible body weighs down the soul, and the earthly tabernacle presses down the mind that muses upon many things?" (Wisdom 9:15) And eagerness, or desire of action, if this is the right meaning to put upon the Greek horme, is also reckoned among the primary advantages of nature; and yet is it not this which produces those pitiable movements of the insane, and those actions which we shudder to see, when sense is deceived and reason deranged?

In fine, virtue itself, which is not among the primary objects of nature, but succeeds to them as the result of learning, though it holds the highest place among human good things, what is its occupation save to wage perpetual war with vices,—not those that are outside of us, but within; not other men's, but our own,—a war which is waged especially by that virtue which the Greeks call sophrosune, and we temperance, and which bridles carnal lusts, and prevents them from winning the consent of the spirit to wicked deeds? For we must not fancy that there is no vice in us, when, as the apostle says, "The flesh lusts against the spirit;" (Galatians 5:17) for to this vice there is a contrary virtue, when, as the same writer says, "The spirit lusts against the flesh." "For these two," he says, "are contrary one to the other, so that you cannot do the things which you would." But what is it we wish to do when we seek to attain the supreme good, unless that the flesh should cease to lust against the spirit, and that there be no vice in us against which the spirit may lust? And as we cannot attain to this in the present life, however ardently we desire it, let us by God's help accomplish at least this, to preserve the soul from succumbing and yielding to the flesh that lusts against it, and to refuse our consent to the perpetration of sin. Far be it from us, then, to fancy that while we are still engaged in this intestine war, we have already found the happiness which we seek to reach by victory. And who is there so wise that he has no conflict at all to maintain against his vices?

READING QUESTIONS:

- 1. What does Augustine mean by saying that he will lay out his argument “from such reasons as can be adduced to unbelievers?” Why would he do this?

- 2. What is happiness (or the supreme good) according to the city of God? How does it criticize those who seek earthly happiness?

- 3. What reasons does Augustine give for denying the possibility of happiness in this life? It is important to see that he focuses on those sources of happiness that the philosophers claimed (the body, the intellect, and moral virtue). Follow his argument against each.